Story structure, examined: Freytag’s pyramid (why tension has a shape)

Freytag’s Pyramid is one of those ideas most writers vaguely remember from school and then quietly file away.

It usually shows up as a triangle on a whiteboard. Rising action. Climax. Falling action. Resolution. Simple enough to feel obvious. Old enough to feel irrelevant. Easy to dismiss as something academic that doesn’t survive contact with modern storytelling.

The problem is that Gustav Freytag wasn’t trying to teach writers how to write.

He was trying to explain why certain stories feel the way they do after they’re over.

Who Gustav Freytag was, and what he was actually studying

Gustav Freytag wasn’t working in film or television. He wasn’t thinking about page counts, audience retention, or opening-weekend momentum. He was a 19th-century novelist and critic looking backward at classical drama.

Freytag studied tragedy, especially Shakespeare. Not to extract a formula, but to observe patterns. He noticed that in these stories, tension didn’t just move forward. It rose, reached a breaking point, and then declined as the consequences played out.

That observation became what we now call Freytag’s Pyramid.

It’s important to understand the assumption baked into it. Freytag treated tragedy as the default mode. His model expects damage. It expects loss. And it assumes the fall matters just as much as the climb.

What Freytag’s pyramid is really describing

Freytag’s Pyramid isn’t a beat sheet. It isn’t an act structure. It’s closer to a pressure chart.

Tension builds. It tightens. It reaches a point of no return. And then the story has to live with what just happened.

Most modern frameworks are obsessed with momentum. Freytag was interested in aftermath.

That’s why his pyramid feels different from three-act structure. Three acts are about movement and progress. Freytag’s Pyramid is about emotional trajectory. What happens to a story once it breaks.

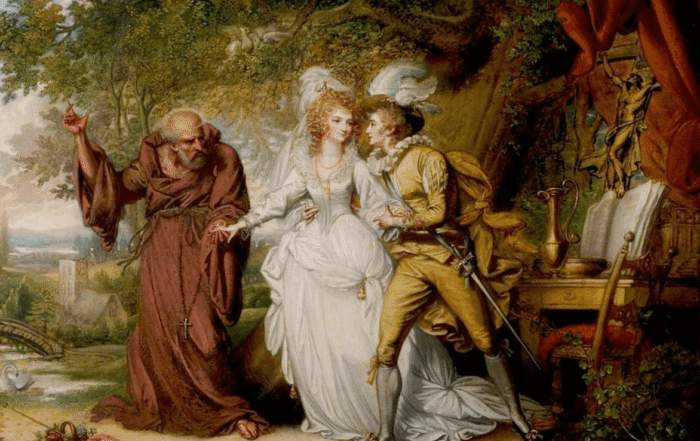

Why Romeo and Juliet fits the model perfectly

If you want to see Freytag’s Pyramid working exactly as he described it, the cleanest example is Romeo and Juliet.

This is the kind of story Freytag was looking at when he mapped the shape.

The opening establishes a volatile world. Two families locked in a senseless feud. Violence baked into everyday life. The rules are clear, even if they’re irrational.

The rising action isn’t just romance. It’s pressure. Love deepens. Secrecy compounds risk. Each choice closes off another exit. Nothing explodes yet, but everything narrows.

The climax comes late, and it’s unforgiving. Mercutio dies. Romeo kills Tybalt. From that moment on, recovery is impossible. This is the peak of the pyramid. Not the most dramatic scene, but the irreversible one.

What follows is the part many modern stories rush.

The falling action matters here. Miscommunication. Desperation. Bad timing. Each event flows directly from the climax. The tension doesn’t disappear. It mutates into dread.

The resolution restores order at an unbearable cost. The lovers are dead. The feud ends. Balance returns, but nothing feels like a victory.

That long descent is the heart of Freytag’s thinking. The story doesn’t end when the damage is done. It ends after we’ve sat with it.

Why Freytag feels out of step with modern storytelling

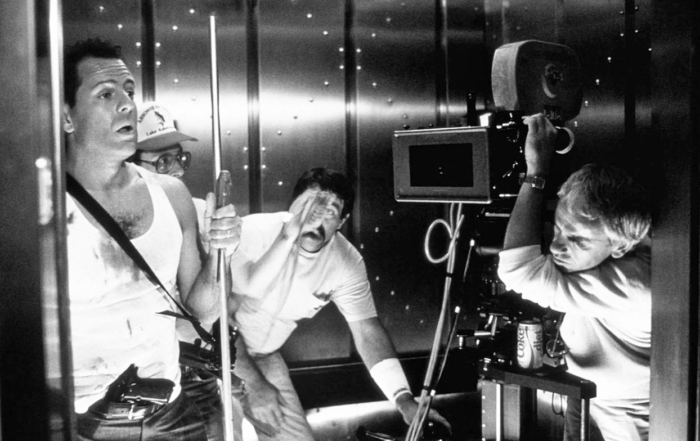

Freytag’s Pyramid can feel awkward when applied to contemporary film and television.

Modern stories tend to compress the fall. Climaxes arrive late, and resolution happens fast. Audiences are trained to expect propulsion all the way to the final frame. Spending time in aftermath can feel slow or indulgent.

That doesn’t make Freytag wrong. It means he was describing a different priority.

His model assumes consequences deserve space.

What Freytag’s pyramid is good for

Freytag’s Pyramid works best as a diagnostic lens.

It helps explain why a climax feels too early. Why an ending feels rushed. Why a story collapses emotionally after its biggest moment and never quite recovers.

It’s not especially useful as a planning tool. Freytag wasn’t telling writers where to put events. He was explaining what happens to tension when it’s allowed to complete its arc.

How it fits with other frameworks

Freytag’s Pyramid doesn’t compete with three-act structure or beat sheets. It describes something else entirely.

Three acts organize time.

Beat sheets manage attention.

Freytag’s Pyramid maps emotional rise and fall.

Together, they don’t tell you how to write a story. They explain why it feels the way it does when it’s over.

Closing thoughts

Freytag didn’t hand writers a formula. He handed them a shape.

A reminder that tension leaves a wake. That the biggest moment isn’t the end of the experience. How long you stay with the fallout changes how the story lands.

That’s what Freytag was noticing.

And that’s why the pyramid still holds.