Story structure, examined: three-act structure

Most writers already know this one.

Beginning, middle, end. Set up, conflict, resolution.

It sounds almost too simple to be useful. And yet it keeps holding.

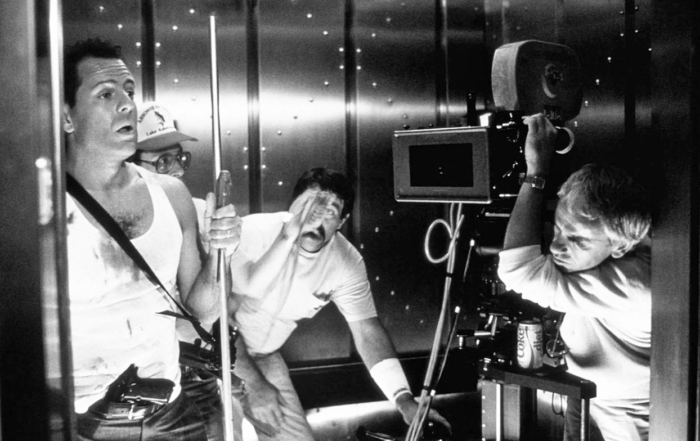

Take Jaws.

- Act one is the promise.

The shark attacks. The town downplays it. The danger is real, but it’s contained, at least for now. This act answers a single question: what kind of movie are we watching? By the time the beach stays open, the audience knows exactly what’s at risk and who’s going to pay if nothing changes. - Act two is pressure.

The shark keeps circling. The deaths stack up. Systems that are supposed to protect people don’t. Brody, Hooper, and Quint clash over methods, money, and responsibility. Nothing gets fixed, but everything tightens. This act isn’t about clever twists. It’s about stress. How long can this situation hold before it breaks? - Act three is commitment and payoff.

They head out on the boat. There’s no town left to hide behind. Everything the story set up earlier comes due. Fear, competence, flaws, and courage collide. The ending doesn’t arrive because the runtime is up. It arrives because the story can’t keep going any other way.

Its power comes from escalation, timing, and release. That’s three-act structure doing exactly what it’s good at.

Where the three-act structure comes from

Three-act structure didn’t begin as an industry rule. It began as an observation.

Long before screenwriting manuals existed, Aristotle talked about stories having a beginning, a middle, and an end. Not as a checklist. Just as a description of how people tend to experience cause and effect. Something starts. Something shifts. Something settles.

That idea lingered for centuries. Then filmmaking turned storytelling into a group effort, complete with schedules, budgets, and deadlines.

In the twentieth century, figures like Syd Field took that old observation and shaped it into something practical for screenplays. Acts became tied to page counts and turning points. What began as philosophy turned into a system people could point to and use together.

At that point, three-act structure stopped being just about story. It became about coordination.

What three-act structure is actually good at

Three-act structure is good at managing time and expectation.

It helps answer plain, working questions. When does the story really start? When does it turn? How long can tension stretch before the audience gets restless? When does the story have to pay off what it set up earlier?

On its own, this framework doesn’t worry much about theme or inner life. Its job is momentum. It keeps things moving and helps the audience stay oriented.

That’s why it shows up so often when a script feels slow, rushed, or oddly unbalanced.

Why it became the industry default

Three-act structure stuck because it’s easy to talk about.

It gives writers, producers, executives, and editors a shared shorthand. The first act sets things up. The second complicates them. The third resolves or reframes them. That shared language makes it easier to discuss pacing and scope without drifting into arguments about taste.

This isn’t really about limiting creativity. It’s about alignment. When a lot of people are working on the same project, they need common reference points. Three acts provide those.

Acts as pressure, not sections

One of the most common mistakes is treating acts like chapters.

They aren’t.

Acts work more like pressure zones. Each one holds a specific kind of tension until the story can’t sustain it anymore. Act one builds expectation. Act two strains it. Act three forces a release or a change in terms.

Page numbers matter far less than the emotional load each act is carrying. When that load gets too heavy, the story has to move.

Thinking about acts this way helps avoid paint-by-numbers plotting.

How three-act structure differs from other frameworks

Compared to models like the Story Circle or the Hero’s Journey, three-act structure is fairly indifferent to meaning.

It doesn’t track inner transformation. It doesn’t care much whether change is symbolic or psychological. It focuses on external movement and escalation.

That’s why it pairs so easily with other frameworks. Three acts organize time. Other models organize change or significance. Together, they cover different layers of the same story.

Where three-act structure breaks down

Three-act structure struggles with stories that resist clean resolution.

Episodic work, elliptical narratives, or deliberately unresolved endings can feel squeezed by a model that expects escalation and payoff. It can also give writers a false sense of safety. Hitting the right act breaks doesn’t mean the story has any pulse.

When it fails, it’s usually not because the structure is wrong. It’s because it’s standing in for a clear intention that isn’t there yet.

How it’s used in development and coverage

In development and coverage, three-act language shows up because it’s fast.

Notes about a sagging second act or a rushed third act give everyone a way to talk about problems without making things personal. It keeps the focus on function instead of preference.

That makes three-act structure especially useful as a diagnostic tool, even when it isn’t the creative engine behind the project.

How it fits alongside other story models

Three-act structure doesn’t replace other frameworks. It sits next to them.

It organizes time and momentum. Other models help define change, meaning, or theme. When writers feel like they’re doing everything “right” but something still feels hollow, it’s often because structure is present and purpose isn’t.

Knowing what each framework is responsible for clears up a lot of that frustration.

Closing thoughts

Three-act structure refuses to disappear because it solves a real, practical problem.

It helps stories move. It helps teams talk to each other. It helps audiences stay oriented. What it doesn’t do is tell you what your story is about or why it matters.

Like any tool, it works best when it fits the job at hand.

Next in the series:

Story Structure, Examined: Beat Sheets (Why Hitting the Beats Isn’t the Same as Telling a Story)